I obtained a self-sponsored EB-2 National Interest Waiver (NIW) green card in 2019, just after grad school, from a F-1 visa. This post summarizes the story of my application, including mountains of paperwork, fees, travel restriction - oh, and waiting! The post was born as ar reply to a fellow JPLer’s e-mail, and it is quite JPL-centric. It was quite cathartic for me to write – hope it will be useful for you as well.

Timeline

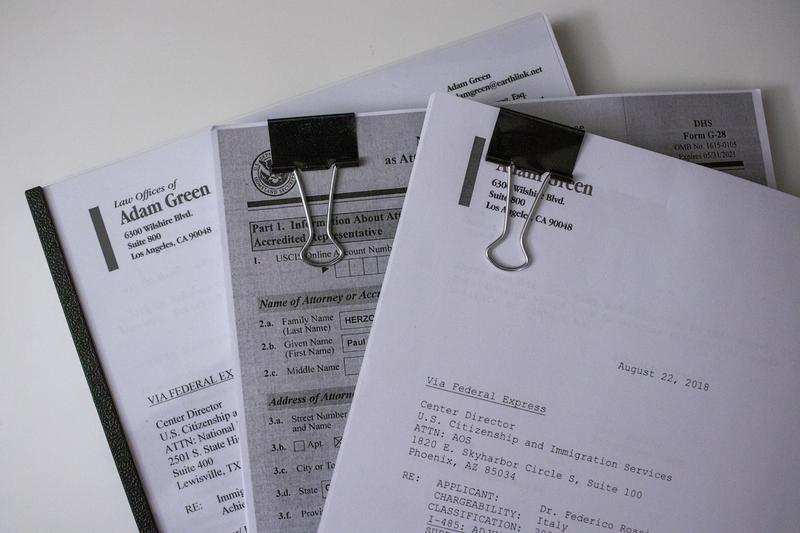

I got my Ph.D. in March 2018, and joined JPL as a postdoc in April 2018. I retained Adam Green’s law firm in April of the same year. I had an interlocutory phone conversation with them the previous summer, and eventually decided to go with them (over a couple of other firms) because Paul Herzog, the lawyer who actually worked on my application, seemed very knowledgeable about the NIW process and has a very good track record working with JPLers on green cards.

I worked on collecting the letters and other supporting material until end of June, 2018. Paul wrote the cover letter and put together my I-140 package in about ~2 weeks, so it was ready by mid-July. I requested some edits, which took another week or so. We ended up submitting the I-140 in early August 2018.

To speed things up, we filled the I-485 concurrently. “Concurrent filing” does not mean that you send both packets at the same time, just that you send the I-485 before hearing back about the I-140. We put together the I-485 in early August, and submitted it by the end of the month. When we submitted the I-485, we also requested a temporary employment authorization document (EAD) and advance parole (AP - together, they make a “combo card”), which give permission to work and travel as one waits for the green card petition to be adjudicated.

In December 2018, I moved from postdoc to full-time staff at JPL.

After months and months of silence, my I-140 was approved on Feb. 28, 2019. When we submitted, we expected a 4-5 months wait, but USCIS all but stopped processing petitions in November-December, so that set us back for a while.

The EAD+AP is normally adjudicated in 60 to 90 days but, for reasons unclear to us, it took until May 2019 for us to get that document. Once we went beyond USCIS regular processing times, we contacted USCIS twice unsuccessfully over two months (they say they can take up to a month to reply - they never got back to us for either request). After those two attempts, we wrote to our local congresswoman, Anna Eshoo. The congresswoman’s office contacted USCIS, and we received the EAD+AP two weeks after.

In mid-May we heard that our green card application was ready for the interview. After a week or so, the interview was scheduled for June 28 (more on the interview below). At the end of the interview, the officer gave us a letter saying that our application was approved. We received our green cards in the mail about a week later, one year ago these days.

Qualifications and Material

When I applied, I had:

- A Ph.D. in Aeronautics and Astronautics from Stanford;

- A couple of journal papers and several conference papers from selective conferences (in my field, conference acceptance rate fluctuates between 25% and 50% depending on the venue);

- fewer than 40 citations of my work;

I collected eight reference letters. Two of these were from JPLers, including my boss and the manager who had hired me. One was from my advisor, and another from an industry researcher who knew my work well (and had tried poaching me earlier). The last four letters were from professors and researchers with whom I had not directly worked, but who had cited my work. I was surprised at how willing they were to write a reference letter, once I explained that the point of the process is to write a recommendation for someone they do not know directly, but whose work they are familiar with. There was apparently an awkward phone call where a big professor I had contacted called my advisor and asked him “who is this rando and why does he want a letter from me?”; but my advisor went to bat for me, and I ended up getting a letter from the professor.

In addition, the lawyer suggested collecting letters from editors of the journals and conferences I had published in, asking them to state the acceptance rate of their venue. I also had a letter from my university’s librarian, which acted as a “cover letter” for the editors’ letters and tried to put my publication record in the best possible light. Finally, I also had letters from each journals/conferences I had reviewed for.

I drafted all of these letters except for one (the amazing industry researcher wrote a beautiful letter of support with no prompting from me). I sent each draft to my lawyer; out of eight letters, the only edit he suggested was the addition of a line break. I would like to think this is a testament to my superb writing skills, but I suspect he may have felt my case was comparatively easy. Once I sent the letters to my referees, they made their edits (minimal in some cases, extensive in others) and sent them back.

I found that it took me about one week of night-and-weekend work to write a good draft for each referee’s letter, and a couple of weeks to get the signed letter back. The editors’ and reviewers’ letters were much easier, basically form letters.

Fees

Overall, I paid roughly $12k. You should expect to pay between $10k and $12k, depending on the lawyer.

Here are the fees I paid in detail. There is a good chance that, by the time you read this, they will be out of date. USCIS fees are posted here. I know of no law firm that publishes their fees, but they are typically discussed pretty early in the initial phone call.

Government fees

- I-140: $700 (for myself)

- I-485: $2450 ($1225 each for me and my wife)

Lawyer fees

- I-140+I485 for myself: $6500. $3k retainer, $3.5k upon submission of I-485.

- I-485 for my wife: $2000

- I believe there was also a “postage and photocopies” fee of a few hundred dollars, I forget the exact amount.

The Law Firm

I worked with Adam Green’s office and was assisted by Paul Herzog. Paul wrote a pretty authoritative (if now out-of-date - Google “Matter of Dhanasar”) article on the NIW process, and has worked with a bunch of JPLers in the past. This post is not a review; if you want to know more about my experience with Adam Green’s office, please do not hesitate to contact me.

Waiting

Once the petition is submitted, the waiting starts. USCIS is incredibly opaque, and the wait can be quite bad from a mental health standpoint.

USCIS has two websites for tracking one’s petition, eGov and MyAccount. They are not in sync (although changes seem to propagate from one to the other within a few days), and either of them may be updated ahead of the other. One of them sends text updates, but the other doesn’t. (and the text update is “there has been a change, log in to see it” - cue elevated heart rate) After a few months, you get into a daily - and then hourly - ritual of checking both websites compulsively.

There are online communities dedicated to tracking the progress of USCIS petitions. The best community I found is trackitt.com, which has a tracker where people post their updates and where you can filter by submission date, service center (the actual USCIS office processing your petition), nationality, etc.

USCIS does go roughly in order of submission, so it can be helpful to track how many months’ worth of petitions they have before they get to yours. At the same time, it is a truly inscrutable process: for instance, when we submitted our petitions in August 2018, USCIS was processing May cases, so we had hopes of getting our initial approval by December; however, based on trackitt tracking, the Nebraska service center all but stopped processing NIW petitions in November and December, for reasons we never understood. Likewise, our EAD+AP should have been processed in three to five months, and other people who submitted in the same timeframe as us did get their travel permit between December and January according to trackitt, but ours didn’t come until May, after the congresswoman got interested. On the upside, the suggestion to contact the congresswoman came from trackitt. Turns out she has a form on her website for this kind of things, so it must be more common than I expected.

In the current political climate, the wait is likely to be long and potentially more uncertain. It does suck, and it helps a lot to talk to others in the same situation - I find that those who haven’t been through the process do not fully grasp how dehumanizing it is, and one builds a strange kinship with the other posters on trackitt and in real life.

Traveling

When I applied, I was on a F-1 visa, which is not dual-intent. That means that that, when you enter the country on a F-1, you can’t have immigrant intent, which is established by applying for a green card. I believe you can have immigrant desire, so long as you don’t act on it - this has been litigated, but I would not want to get into that debate with a border officer.

You can apply for a green card from a non-immigrant visa once you are in the US, but you need to keep two things in mind:

- If you apply within 90 days of entering the US, the government will presume that you lied when you entered and may reject your application and cancel your previous visa. It used to be 30 days until 2017 or so, but alas. If you apply after 90 days, there is a presumption that you had no immigrant intent when you entered the country, and just changed your mind later.

- Once you apply, traveling is problematic. If your visa sticker expires, you will most likely not be able to receive a new one. If you have a valid visa sticker, opinions differ on what may happen at the border; I believe Paul advised me that I should be able to travel, but I did not want to risk it.

This is a concern for all non-immigrant visas, e.g. F and J. It is not a concern for dual-intent visas, e.g. H-1B.

The interview

Our interview was a pure formality. Here are my contemporary notes from just over a year ago.

The interview happens at the federal building in downtown LA. We were sworn in, the officer took our pictures and fingerprints. Then we went over the I-485 we had submitted (which has something like a hundred yes-no questions like “have you been a Nazi in WW2” and “have you profited, or has your parent or spouse profited, from child soldiers?”). We made small changes as needed (address, employment dates). The officer asked us the questions from the I-485 in groups (“have you ever had any run-ins with the law?”, “have you ever trafficked drugs or weapons?”). I had switched visas and moved from postdoc to staff since the submission - he made copy of my new employment letter and H-1B approval, passport, and ID.

At the end of the interview, the officer printed and gave us a letter saying we were approved. As we went back home, the status on one of the two USCIS websites (but not the other) changed to “new card is being produced”. The othere website caught up three days later.

We got our card in the mail about a week later and, once I presented it to JPL security, I officially became a US person in the eyes of the lab.

The bottom line

Getting a NIW green card was probably my best decision so far career-wise. It smoothed my transition from postdoc to staff (being able to say “I am in the line, and pretty confident I will be approved within six months” helped a lot, I am told), and being a US person at JPL gives a lot of access to the incredible pool of latent knowledge on lab. A week after I became a US person I was in a meeting with Fred Calef, who is the “Keeper of the Maps” (actual title!) for MSL, as he told me in great detail exactly how Curiosity knows where it is on the surface of Mars. It felt so amazing to hear this information without having to worry about “can I know about this?”, “Is this on my TTP?”, “Am I going to get in trouble?”, “Is anybody going to get in trouble?”. Access to this knowledge is what JPL is all about.

I still haven’t run the full length of Bldg. 301, but I fully plan to do so once we are back on lab.

Incidentally, my wife had an informal visit/quasi-interview at JPL the day before our green card interview (when we strongly felt that it was a done deal) and, some time after that, she was hired on lab as a US person. It would have been borderline impossible for her to join JPL as a FN, and now she works on Clipper and SphereX (while I still do R&TD work - I am a bit jealous sometimes).

I am PI-ing a couple of very small projects and am experiencing first-hand how complex it is to have FN teammates from the other side. You need to get an export classification from Export Control and fight them down from ITAR to EAR to EAR-99 (or apply for an export license, which takes six months); you have to use a special version of Github; you are supposed to document every interaction with a FN (getting coffee with them? if you are talking about work, you should write it down, in case we get audited); and, if you want them to help with a new project, time to get a new Technology Transfer Plan.

With a green card, all of this goes away - you get to experience first-hand the incredible knowledge that JPL stores, and fully contribute to growing it.